Cars are an urban disease. Need proof? Just try parking in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood in the rain.

You'll find yourself not only anxiously turning down the radio, head whipping from mirror to mirror, but also among the exasperated third of urban drivers, who are also looping the block in the hunt for a spot. Building more parking won't fix the problem, nor will expanding roads.

More parking and more lanes only means more drivers and more cars. More pollution. More noise. More carbon emissions. More divided neighborhoods. More of this mess we’re in.

So we should take the bus instead. We should advocate for bike lanes. We shouldn’t drive, and when we do, we should know that we are a problem.

And still, knowing this, and having endured the irregular-heartbeat inducing gasp of seeing an open spot that was just too small for our RAV 4, or with a red painted curb, or marked, I realized, deflating, for loading and unloading, there's something fortress-like and oh-so pleasantly interminable about sitting in a parked car.

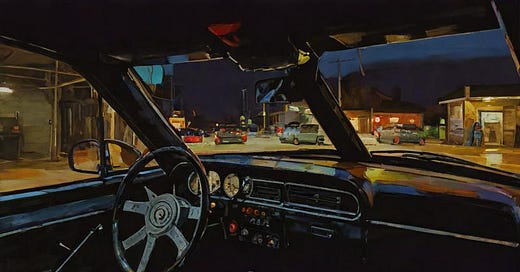

The beeps and honks and blinkers and hissing busses raging in your ears just a minute before somehow can't penetrate the motionless windshield as it collects the evening drizzle and the misty glaze of your breath. Even the reserved spot in our building's parking garage, far from the chaos of Capitol Hill, beckons me, “just sit and be” for a minute–or twelve–after I cut the engine.

Why?

Perhaps the answer is nostalgia. When I was a kid my family would road trip from Baltimore to central Ohio to see our grandparents for the holidays. I'd always try to sleep on the drive home, my head lolling listlessly next to the sticky plastic cup holders of our gray Honda Odyssey. But I never slept as deeply as the instant my Dad put the car into park. Something about the comfort of arrival, the mid-beat cut of the engine–and yes, perhaps, the naive hope that I could avoid having to unpack the minivan–plunged me deeper into restfulness.

But I'm certainly not nodding off when I pull into our parking spot on a Tuesday afternoon (most of the time, anyways). How then does the front seat of the car become such a meditative space?

Perhaps I'm still trying to avoid unpacking the car–the luggage I let my parents haul up the stairs instead now the voices and screens inevitably pulling me from other screens waiting outside, back in the world beyond the dashboard where everything seems to insist the future is bleak and driving is a crime that can't be helped.

But in my parked car–that liminal space devoid of responsibility and thus regret–time stops. I can listen, completely now, to the final verse of that John Cragie song, or the end of Ross Gay's Catalogue of Unabashed Gratitude, or the otherwise-fleeting silence.

It used to be here, bathing in the quiet, my seatbelt often still buckled, where I would forget that cars kill, in more ways than one.

Car accidents are the leading cause of death for people ages one to 54 in the US. And it’s not just drivers and passengers. Almost 20% of the 43,000 people who die in car accidents each year are pedestrians or cyclists. It's but one of too many physically cruel manifestations of power and privilege in our world: One in four Americans lack transport to consistently get where they need to go. 90% of pollution-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. Worldwide inequality is as high as it was during the gilded age.

And yet only two thirds of Americans voted in the last presidential election. It was the highest turnout in over 100 years. A growing percentage of would-be parents are choosing not to have kids because of climate change.

Something needs to give. Yes, to the economic and transport systems that leave too many behind, literally and figuratively, and also to the fatalism they inspire.

So recently I’ve tried to reject these voices that say the world is terrible and the future doomed, that we probably shouldn’t have kids and we definitely shouldn’t drive. Perhaps it’s the way I feel my progressive community abandoning my liberal values, but I’m trying a new habit of questioning my quick trigger distaste for so many of the things I'd once thought were a scourge on society, including capitalists, conservatives, and yes, cars.

Instead, I've tried to cautiously appreciate the enormous bounty our so visibly flawed society has given so many. Indeed, it has deprived others in equal measure. But I think holding that both can be true, that cars can kill and pollute and divide and calm and connect, inclines me towards optimism and away from the spirit of grievance–drunk uncle to polarization and pompousness–I so recently shared with many of my friends. Call it naivete. Call it privilege (it most certainly is). Call it getting older.

Whatever the name or cause, I've found that with this shift in my mindset the remorse that plagued me like a shadow around the roads of the Northwest has been replaced by appreciation–tender aunt to compassion. But it’s not just that I feel less guilty. If that were all this essay were about, I’d be a real jerk.

It’s that as and perhaps because I appreciate–even more now–being able to take our car out of the city to ski and explore, and I relish the chance to sit in our garage afterwards to the finish the song or my thought or to soak in the quiet, lately more than ever, if I have an errand close by, I no longer drive and feel guilty.

I bike or take the bus.